The Devouring Sea: Drowned by Tentacles and Gods

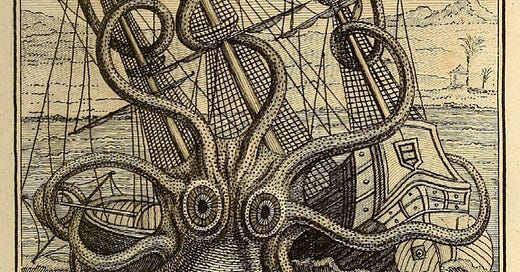

Figure 1: A 19th-century engraving depicts a ship ensnared by a colossal octopus – a fearsome “kraken” dragging the vessel to a watery doom.

The open ocean has long been imagined as a voracious maw, lurking with tentacled monsters and vengeful deities. In Norse legend, sailors whisper of the goddess Rán, ruler of the deep, who casts a net to drag the drowned down into her realm. In one evocative illustration by Johannes Gehrts (1901), Rán is enthroned on skulls and coral, her net reaching up through the waves to entangle a hapless castaway clinging to a broken mast. The sailor is doomed – the mast will soon tip, and Rán will haul him into darkness along with the souls of all she has robbed from the surface world. Such images personify the sea as an indiscriminate taker of life, a feminine force analogous to death itself.

"Ran" (1901) by Johannes Gehrts. The sea goddess Rán pulls men into the sea, where they meet their watery doom among the bones and corpses of others.

This motif of the hungry ocean reached a grotesque apex in Enlightenment-era lore. In 1801, French naturalist Pierre Denys de Montfort published an infamous engraving of a poulpe colossal – a giant octopus – wrapping its monstrous limbs around a sailing frigate. The kraken’s tentacles coil up the masts and hull, preparing to yank the ship into the abyss. Montfort’s illustration blurred science and myth, feeding an enduring terror of what “threats from the deep” might seize those who venture across the waves. As Johannes von Müller observes in Disaster of the Sea, the shipwreck became a defining nightmare of modernity: human voyagers abducted from the habitable world above and pulled into the hostile world below. The kraken and Rán embody this devouring sea – a churning chaos that reaches up to claim lives and ships without warning.

The Sea Subdued: Nets, Knowledge, and Dominion

Figure 2: Renaissance fresco (Camera dei Venti, Palazzo Te, 1528) – fishermen haul up a heavy net, even snaring a mythic sea creature in their catch.

In stark contrast to the sea’s fury stands the image of the sea as dominated – a bounty to be harvested and a mystery to be mastered. Renaissance art often celebrated this human dominion. In Giulio Romano’s Camera dei Venti fresco for the Duke of Mantua, robust fishermen pull bulging nets from the water, straining under the weight of gleaming fish – and even a writhing sea-monster – lifted up into the world of air. Here the ocean’s denizens are overpowered by human technology, hauled to the surface in nets rather than dragging men below. As Müller notes, such nets in art became symbols of “dominion over the fish and the sea” – whether economic, epistemic, or even religious. The Biblical echo is clear: “Fishers of men” and stewards of creation, humanity asserted a God-given command over the waters.

During the Enlightenment, this confidence grew into a drive to catalogue and control. The very act of knowing the sea was likened to casting a net. Naturalists like Carl Linnaeus devised taxonomies that spread like an invisible net over nature, catching each species in the mesh of scientific names. The 1686 frontispiece of Francis Willughby’s Historia Piscium (History of Fish) encapsulated this spirit: myriad fish are arrayed before learned men on a ship, as if scooped from the sea by knowledge itself. Knowledge became a net that could capture even the elusive denizens of the deep.

This triumphant image of subjugation also found allegorical form in Baroque art. In 1754, sculptor Francesco Queirolo carved Il Disinganno (“Release from Deception”), a marble tour-de-force featuring a man entangled in a delicate net. An angel helps peel the marble net off him, symbolically liberating his mind from ignorance. Notably, the net here represents the binding forces of nature and illusion, which the enlightened human spirit must cast aside. The sculpture’s message is emancipation: by shedding the net, humanity throws off the deceptions of the physical world and rises toward divine light. The net thus served as a potent dual symbol – on one hand, humanity’s tool to dominate the sea and acquire truth, and on the other, a web of worldly snares to be overcome by reason and faith.

Francesco Queirolo. Detail of Il Disinganno (Release from Deception). 1753-54. Marble. Cappella Sansevero, Naples.

Where Tentacle Meets Net: Reflections and Reversals

The motifs of the devouring sea and the dominated sea were not separate, but entwined in a dialectical dance. Tentacle and net form eerie mirror images. The net, a human invention to tame nature, finds its dark reflection in the tentacle – a “phobic counter-image”, as Müller writes, embodying nature retaliating in kind. In the mythic imagination, every net cast into the ocean spawns a tentacle rising to tear down a ship. The kraken’s coils are a net in reverse: where the net hauls creatures out of the depths, the tentacle drags humans down into them. It is an uncanny inversion – the tool of dominion answered by an agent of chaos.

Müller’s analysis highlights how artists eventually placed the net into Rán’s own hands. In other words, the sea’s devouring force coopts humanity’s instrument of mastery. The Norse goddess, once content to seize swimmers with bare hands or storms, now wields a fishing net as her emblem of power. This inversion acknowledges an underlying fear: that the subjugation of nature might provoke nature’s revenge. Notably, both the net and the tentacle were often gendered feminine – a reflection of deep-seated cultural anxieties about the wild, “unruly” sea as a woman resisting patriarchal control. In Rán’s case, the feminine sea-goddess turns the tables, ensnaring the (male) voyager with the very device intended to exploit her realm. The result is a kind of cosmic irony, a “fishing for men” that transforms into drowning, as “fishing is flagged as a state of drowning”.

This dynamic interplay persisted into modern artistic and environmental discourse. Contemporary installations like Joana Vasconcelos’ “Valkyrie Rán” (2016) dangle gigantic crocheted tentacles through museum halls, inviting viewers to imagine themselves caught in the sea’s embrace. In Müller’s words, the artwork stages an encounter between the tentacles and the audience, whose very bodies “contain a material net in the form of microplastic particles”, making us the catch of our own nets. Indeed, the literal nets we have cast into the oceans have frayed into invisible snares inside us: scientists report that 66% of marine life is threatened by discarded fishing gear, and those nets degrade into microplastic that infiltrates the flesh of sea creatures and humans alike. The ocean we sought to dominate with nets has effectively invaded us; the net has become internal, a pollutant circulating through blood and plankton in a grim reversal of fortune. In this way, the “disaster at sea” imagery of old has morphed into a very real “disaster of the sea” – one where the sea is victim and humanity is the oblivious perpetrator caught in its own trap.

Yet there is a poetic justice in these dual motifs. The sea-as-devourer and sea-as-dominated were always two sides of one coin, each haunting the other. Our ancestors populated the depths with ravenous krakens and grasping goddesses as if sensing that nature would respond to hubris with equal force. At the same time, they threw nets into the sea and over its mysteries, asserting control even as the waves whispered of rebellion. Today, those old stories and images take on new meaning. The sight of a whale ensnared in drifting nets or an ocean choked in plastic is a modern kraken story – the tentacles of our industrial age coiling back toward us. The sea’s two faces, devouring and dominated, converge into one urgent vision. It is a moral seascape, as Müller’s chapter suggests, that reflects our own dual capacity for exploitation and reverence. In confronting these vivid images – Rán’s net and the fisherman’s net, the drowning and the fishing – we are prompted to recognize the delicate balance between humanity and the sea. The ocean’s wrath and its submission are both ultimately mirrors, urging us to humility. Only by heeding those age-old tales can we hope to calm the waters we have troubled, and find a new concord with the living sea.

Sources

Müller, Johannes von. “Disaster of the Sea: The Dual Motif of Drowning and Fishing.” Moral Seascapes, 2024.

Gehrts, Johannes. Rán (illustration, 1901) – in Felix Dahn’s Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen.

Montfort, Pierre Denys de. Histoire Naturelle des Mollusques (1801) – “Poulpe colossal” engraving.

Giulio Romano. Camera dei Venti – Pisces (fresco, ca. 1528), Palazzo Te, Mantua.

Queirolo, Francesco. Il Disinganno (The Release from Deception, 1754), Cappella Sansevero, Naples.

Additional references: “Fishing nets are one of the greatest polluters.” The Economist, 2023; Reichle, I. “Microplastics and Marine Life.” Journal of Environmental Art, 2021.